NOTES ON CINEMATOGRAPHY, LANGUAGE, AND MOMENTS BEHIND THE CAMERA

on set of RESULTS in Marfa, Texas, 2014

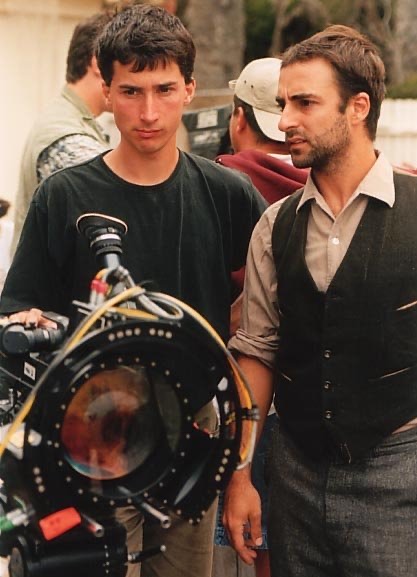

Matthias Grunsky with director Jorge Gaggero filming their thesis film at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles, 2001

SEEING BEYOND WORDS

Cinema has always been my language—even when spoken words failed me. When I first came to the U.S., I often struggled to grasp the nuances of English. Communication on a film set is crucial—every misunderstanding can ripple into mistakes. Yet I soon realized that film itself speaks in a deeper, universal language. At film school, I began collaborating with the gifted Argentinian director Jorge Gaggero. Our first film was entirely in Spanish; our lead actor spoke only Spanish. I knew the story and the scenes by heart, yet on set I understood little of the dialogue. And strangely, that absence of words sharpened my vision. Without the distraction of language, I could read the emotions, the silences, and the truths between the lines. For me that is the essence of cinema.

Later, at the Berlin Film Festival, I met Stéphanie Chuat and Véronique Reymond—two filmmakers from the French part of Switzerland. Working with them, I often found myself surrounded by rapid French discussions I could not follow. But those private exchanges allowed me to focus fully on light, image, and rhythm. We have worked on several projects together where nearly everyone around me spoke French. Again I understood little of the words, but I felt a lot—the tenderness, the humor, the fragility of the people in front of the lens.

I experienced the same in Rio de Janeiro, where almost the entire crew spoke solely Portuguese. I remember sketching beams of light with my hands in the air to my gaffer—and he understood. Because film, at its core, is not built on words but on vision, rhythm, and emotion. So maybe one could say, that in every language I don't speak, I have learned to see the world from a new perspective.

with 2nd AC Ryan Croci, key grip Dan Siegelstein, 1st AC Jack Lewandowski on the set of THE HONOR FARM in Texas, 2019

THE FIRST TIME I LOOKED THROUGH A PROFESSIONAL FILM CAMERA

My very first time on a film set was when I was seventeen.

I was lucky enough to land a summer job as a camera trainee, proudly carrying tripods and silver cases for the camera assistant. I still remember the peculiar smell of undeveloped raw film, the surprising lightness of a 16mm Aaton camera once its lens and magazine were removed, and the magical whir of the camera coming to life. Everything felt more enchanting than I had ever imagined.

After a week, when I began to feel a little braver, I found myself drawn toward the camera sitting silently on a dolly during a blocking rehearsal. Bit by bit, I moved closer, until finally I dared to look through the viewfinder and even pan with the action. Suddenly, I realized the entire crew was staring at me. Later, I received a stern lecture: you never look through the camera without asking unless you are the cinematographer or director. Had I been a paid crew member, they said, I would have owed everyone a round of drinks. I was intimidated, of course, but I also understood something essential: the deep respect the crew had for the camera, and for each person's role around it.

Today, things are different. Big monitors sit on set, often sharper than the camera's own viewfinder. It's almost impossible to keep the entire crew from watching, commenting, and sometimes drifting into distraction. Used with discipline, video villages are undeniably very useful. But sometimes, with a touch of melancholy, I miss the days when the camera itself held the mystery. When its viewfinder revealed images only to the chosen few, and when watching dailies together the next day was a very exciting moment for everyone.

on set while filming AMERICAN ZOMBIE in Los Angeles, 2006

THE CHAIR I NEVER SAT ON

In 2006, I shot my first movie in Los Angeles, "American Zombie", directed by Grace Lee, who I had first met at the Berlin Film Festival. The concept of the film dictated its style: what the audience sees is the raw footage of the documentary crew, who themselves are characters in the story—following not people, but zombies.

From the very beginning, we committed to authenticity. We chose the Panasonic DVX 100, then a popular digital video camera, because it was exactly what real documentarians would have used. My challenge was to balance the realism of a vérité documentary with a growing sense of strangeness, as we descended deeper into the world of the undead. I pursued this with progressively longer lenses, darker, more contrasty lighting, and flickering fluorescent fixtures that crept into the imagery like nervous ticks.

The paradox was striking: on one hand, I had a tiny MiniDV camera in my hands; on the other, a full lighting truck, a documentary-sized camera team, and a feature-sized grip and electric crew. I was even given my own director's chair. But I never sat on it. It became a script stand instead, and our assistant director, Christian Lohf, began calling me "maestro," because my posture leaning over the pages reminded him of a conductor leading an orchestra.

Our largest set was a zombie festival, staged on a movie ranch north of Los Angeles. Production designer Nathan Amondson and his team built an eerie carnival world, while my gaffer, Mathew Rudenberg and his electricians, spent days running cables and hiding fixtures across the vast area. Fewer extras arrived than we had hoped for, so we embraced the absence—flooding the grounds with fog, deepening the shadows, making the night itself part of the cast.

I remember one long-lens shot, peering through the crowd and the fog as the night was nearly over. The frame was filled with movement, shadow, and haze. And in that moment—even though I knew every trick behind it—I felt a flicker of fear myself.

an "image shaker" on the set of TALES OF FRANZ in Vienna, 2021

TECHNOLOGY

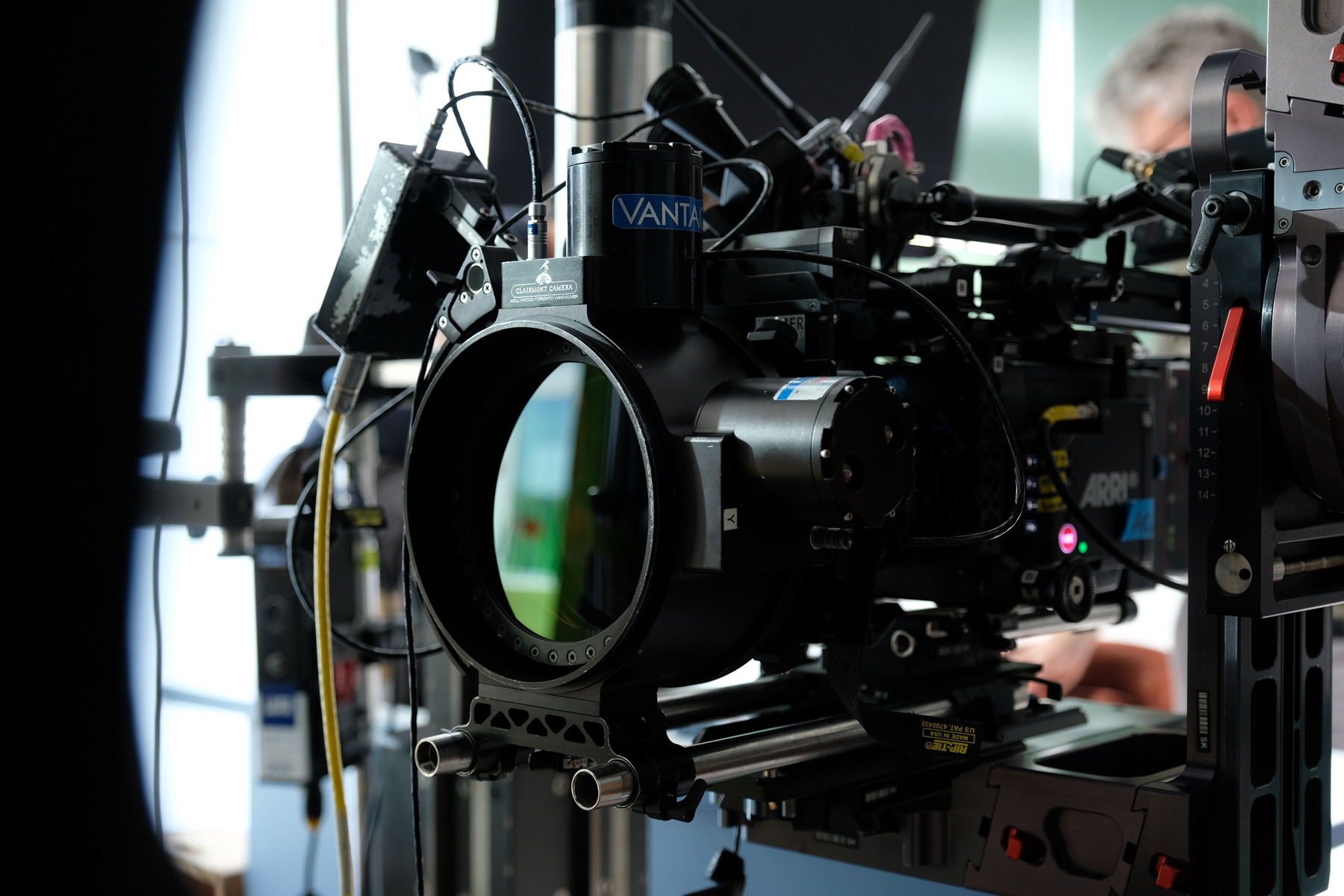

Cinematography has started with and came out of technology, with the invention of the stroboscope in 1830 and later 1891 with the Kinetograph. It was mainly a technological invention and the first fascination with it was the ability to capture movement. Eventually films were made with the intention to tell stories and then more and more complex ones, where technology still was an essential and necessary tool, but the stories with all their emotions and how they were visually told, became what really attracted audiences to the cinemas of the world.

Technology today changes much faster than it used to. A new camera model might be out of date in a couple of years. There are exhibits and demos all the time where manufacturers come up with more, more resolution, more sensitivity, 3D, smaller, lighter, cheaper, faster…. And most of those new products are real improvements and can make the life of a filmmaker much easier if they are available and affordable for the project.

When I start thinking about a script though, technology is not an issue at first, I concentrate on the story the director wants to tell and most of that is very emotional, figuring out the essence of the scenes, notes of feelings. Then in a later step when the director and me have ideas what we want to do, I start to make a plan on how we can achieve it and then the selection of tools comes into the picture. But I never want to approach it the other way around. Of course a lot of times practical reasons determine the equipment list. It is the budget that forces a lot of decisions and some other realities.

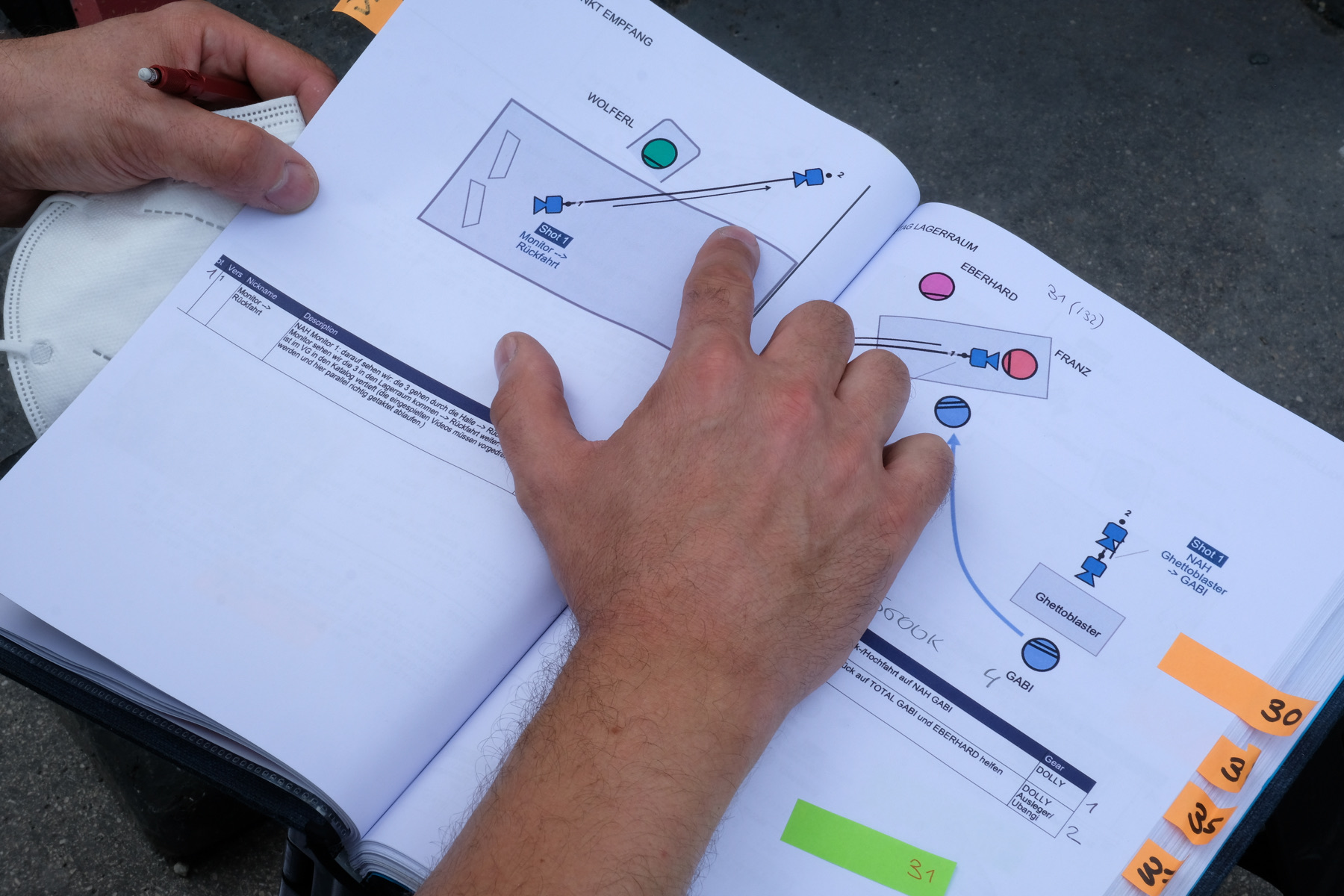

my script on set of TALES OF FRANZ in Vienna, 2021

SERENDIPITY

I like to be surprised in the moment, when reading a script for the first time, without thinking in a mold, like what the producer wants this movie to be, what other movies could be a reference etc., just reading it as a reader/as the audience. I also approach locations at scouts that way, I take pictures, observe and explore, search for angles, often finding myself on the opposite corner of the room than everybody else and always being the last one in the group, falling behind, because I need the most time. Later then I am thinking about the script with those photographs and talk with the director about ideas and options. I find that process very exciting.

When taking stills, you can just capture moments as you find them. You can’t quite do that when shooting a movie with all the elements and schedules. But during prep and on scouts I take stills and find moments, angles, light situations, moods. And I try to spend as much time as possible on locations during prep. Then I select from my collected impressions and ideas and hopefully manage to use some of those thoughts in the movie by re creation, picking the right time to shoot, planning around the elements I like.